Are you curious to discover the prisons of the Doge’s Palace in Venice? Do you want to know how trials were held, where the inmates lived, and how to visit the prisons?

You have come to the right place. I am Paolo from Palazzoducalevenezia.com, and in this article I will tell you about the prisons of the Doges’ Palace.

You’ll find out what the Pits and Piombi are, how trials were held, how inmates were treated and where they were locked up, and you’ll find out how to buy a ticket to the prisons.

Before we begin the article, a brief introduction; if you wish to visit the prisons of the Doge’s Palace Venice, you have two options:

- Purchase the ticket to the Doge’s Palace: that is, the entrance ticket to the Doge’s Palace, which allows you to enter the Palace, visit all the rooms and have a look at the prisons;

- Purchase the ticket for the Secret Itineraries of the Doge’s Palace tour: this ticket allows you to discover, together with a tour guide, the entire Doge’s Palace and take a very in-depth look at the most hidden rooms and prisons in Venice.

If you are interested in discovering the history of the Palace and taking an in-depth look at the prisons, I recommend that you buy the entrance for the Secret Itineraries; if, on the other hand, you want to make a cursory visit to the prisons and have little time for your visit, you can opt for the standard ticket. In both cases, however, I recommend that you purchase the ticket online, to avoid the long lines that may form at the ticket office.

Visit to the Doge’s Palace and Prisons Venice: tickets for the Doge’s Secret Itineraries

Purchase online. Choose your preferred time. Visit Venice’s Doge’s Palace, Bridge of Sighs, prisons and more. You can cancel for free up to the day before your visit.

Well, after this introduction, we are ready to begin our journey inside the prisons of the Doge’s Palace in Venice. Are you ready? Let’s get started!

Table of content

The Palace of Prisons in Venice

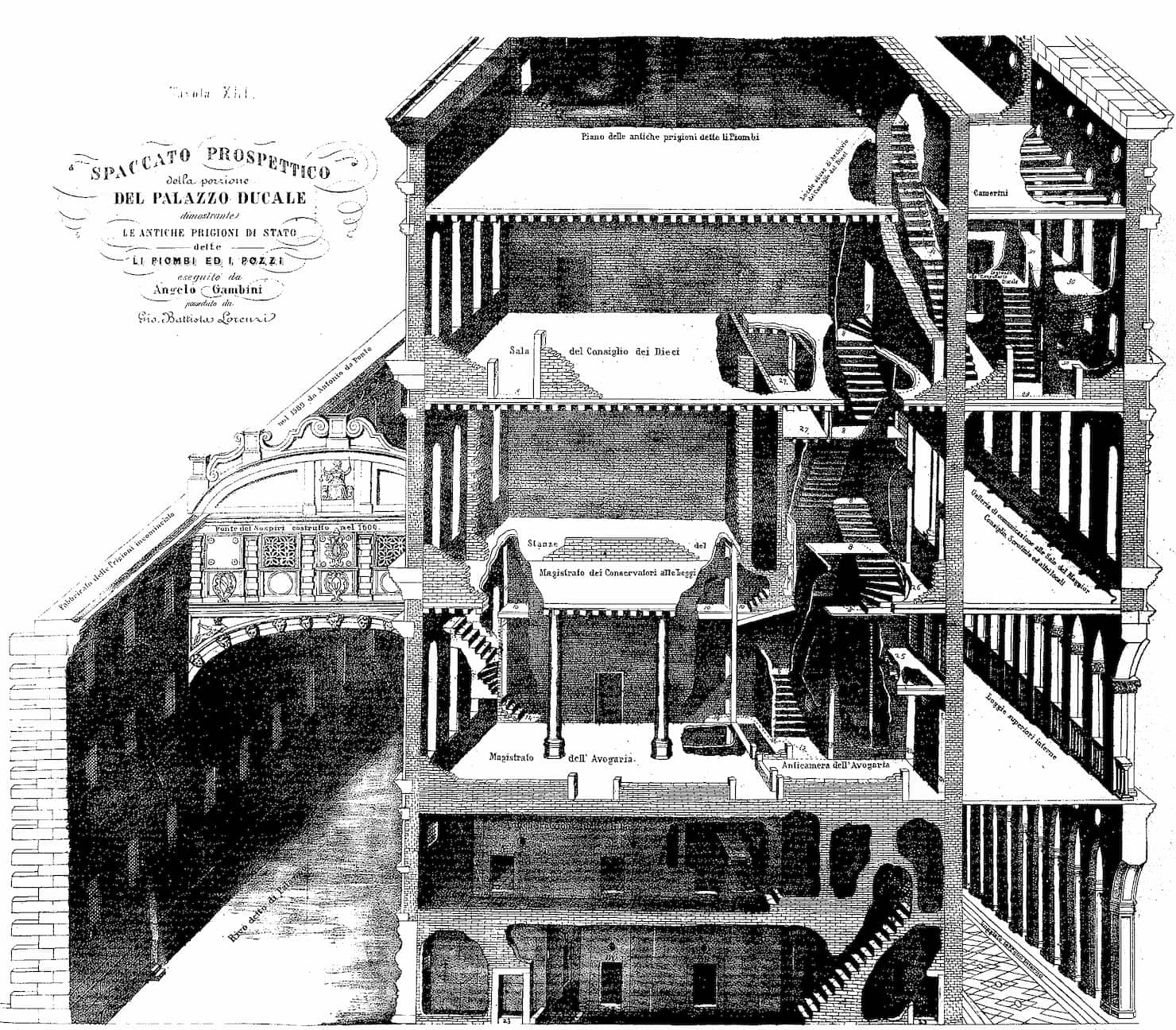

The interior of the Doge’s Palace housed many places of detention, mostly concentrated on the ground floor in cramped spaces that were meant to accentuate the prisoners’ punishment.

After the Prisons were built, only two areas for prison purposes survived:

- the Pozzi, close to the canal, damp, dark, unhealthy, with vaults so low that no upright posture was possible;

- the “Piombi” (“leads” in english), located in the attic, named after the metal of the roofing slabs, where the temperature reached extremes, very cold in winter and muggy during summer.

Are you curious to know how prisoners’ life was carried out during the strict Republic of Venice ?Let’s get started!

Venetian Justice

Inside the Doge’s Palace in Venice, justice was administered, and all judicial, civil, and criminal proceedings took place. Venetian justice was very strict, and trials could also begin as a result of anonymous complaints mailed into special marble lion mouths, real mailboxes.

The court cases were analyzed and discussed in the austere Upper Chancery Hall (located at the square Atrium and the Golden Staircase room). This hall was located in a place that was not easily accessible in the Palace and could be visited via the Secret Itineraries route.

On the walls of the hall were the cabinets that held the public and secret acts of the Venetian magistracies, including the secret archives of the Council of Ten, a much-feared body in Venice along with the magistracy.

Next to the Chancery Hall was the torture room, also called the “Torment Chamber,” entirely lined with wood and with a very high ceiling. The most common technique for extorting confessions from prisoners was the “rope method,” prisoners’ hands were tied and slowly pulled up until they found themselves hanging in the void. A balcony runs around the room; the prisons faced right onto it so that inmates could hear the tortured men’s screams of torment so that they would immediately admit their guilt.

Equally dreadful was the so-called “drop torture,” by which the inmate was immobilized in a chair for hours on end while an icy drop fell on his forehead without his being able to rest or sleep, until he went insane.

Torture, at any rate, was always practiced in mild form in Venice and was gradually abandoned from the seventeenth century onward.

Visit to the Doge’s Palace and Prisons Venice: tickets for the Doge’s Secret Itineraries

Purchase online. Choose your preferred time. Visit Venice’s Doge’s Palace, Bridge of Sighs, prisons and more. You can cancel for free up to the day before your visit.

The prisons of the Doge’s Palace in Venice

Once judged and found guilty, inmates were escorted to the prisons.

If the crimes were minor, these were served in the neighborhood prisons, that is, of the various “Sestrieri” (neighborhoods) of Venice.

Each had its own, also depending on the type of crime, for example, debtors were entitled to the prisons of St. Mark’s, located at the “Mercerie”, while war enemies were entitled to the “Gabioni of Teranova”, on the Schiavoni shore.

More serious crimes, on the other hand, were served inside the Doge’s Palace with different placements depending on the offenses and the social background of the offender: on the ground floor of the Palace were the Pozzi in which the perpetrators of the most serious crimes were locked up, the Piombi located in the attic were for prisoners of regard or those who had committed non-serious crimes, while from the 16th century the New Prisons were built, beyond Rio di Palazzo.

The Pozzi

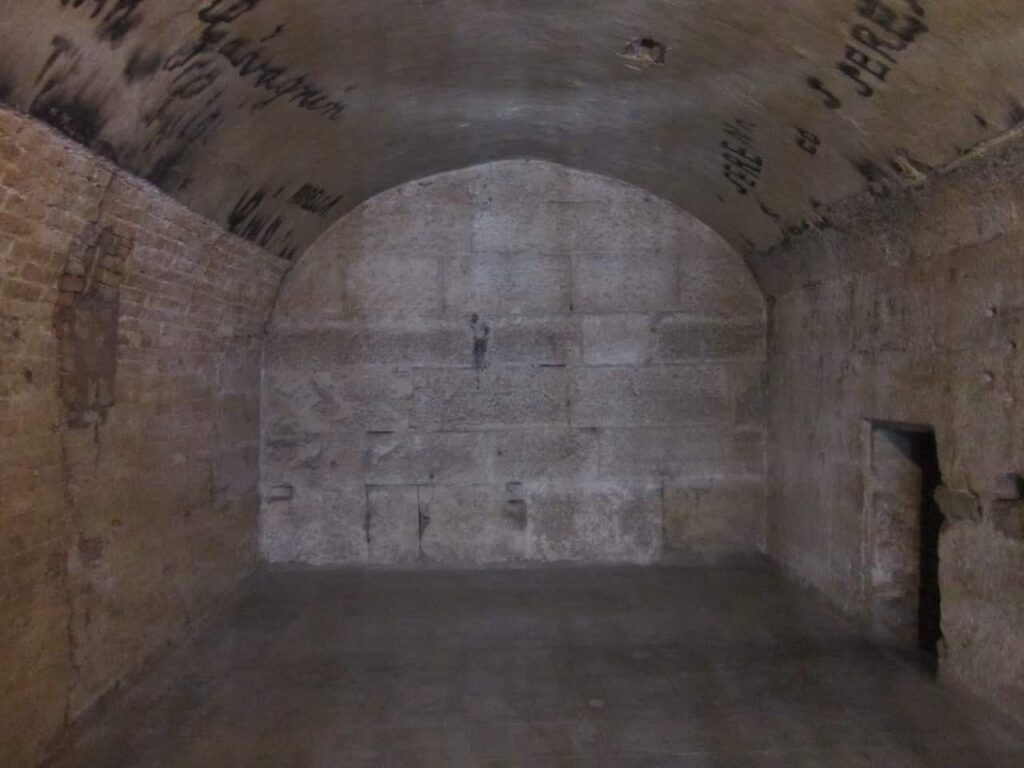

The Pozzi were a group of 18 cells also called “orbs” or “forts” divided into two floors.

The structure, located on the ground floor of the Palace, was concentric with the cells positioned in the center and a perimeter corridor through which the keepers controlled the inmates and distributed food rations to them. This arrangement meant that the inmates could never enjoy sunlight except through a few square windows placed on the corridor.

The cells were tiny and the floors so low that they prevented standing. Inside them was a single board to serve as a bed, a shelf, and the bugliol.

The inhumane conditions in which the inmates were forced were inevitably the cause of insanity, disease and death for the wretches who were “buried” there and whose miasmas could be felt even in the courtyard outside the building.

The only positive note: the constant temperature of the interiors, lined with wood, which at least insulated them from both cold and heat.

Inside the cells it is still possible to observe the engravings and graffiti of the people who were locked up there, sometimes even real works of art. One example is that of the walls of cell X, in which, following a restoration, sixteenth-century nail-engraved graffiti was found depicting the Virgin and Child surrounded by Saints Roch, Sebastian and Benedict, while on the opposite one Christ on the Cross with Saint Roch holding a bell flanked by two pigs.

The work belongs to the hand of Riccardo Perucolo, a young fresco painter from Conegliano. In the mid-sixteenth century he was locked up by the Inquisition accused of Lutheran heresy. Terrified by torture and inhumane cell conditions, he quickly confessed his crime and was soon freed.

However, although he continued to live pretending to adhere to the Roman faith, he was discovered 20 years later and sentenced to be burned at the stake in 1568.

The Piombi

Passing through a series of narrow passageways, one arrives at the upper dungeons, known as the Piombi (the name comes from the metal from which the roofing sheets placed over the larch boards of the attic are formed).

The Piombi were a group of six to seven cells in which the accused awaiting trial by the Council of Ten or the State Inquisitors were housed.

As with the Pozzi the structure was concentric, with a perimeter corridor and the cells placed in the center.

This time, however, the spaces were lit by artificial lights and also by natural light coming from the roof windows, placed perfectly in axis with those of the cells.

The Piombi inmates enjoyed certain privileges; they could have food and items delivered from outside, and they could have a small amount of money with which they could ask the keepers for certain errands. A small infirmary was also present.

The most famous inmate housed in these cells was surely the libertine writer Giacomo Casanova, imprisoned for suspected espionage activities, who by drilling a hole in the ceiling with the help of an accomplice, reached the roof and managed, by passing through a dormer window, to reach the Square Atrium and escape after being mistaken for a lost visitor to the Palace. The heroic adventure was later recounted in his book “The Story of my Escape,” published in 1788.

Other famous people locked up those cells were Daniele Manin, Nicolò Tommaseo and Paolo Antonio Foscarini.

The New Prisons

The prisons inside the Palace soon proved insufficient to accommodate the ever-increasing number of inmates, not to mention the poor conditions of the prisoners inside.

Overcrowding, the risk of fires from fires lit in an attempt to get warm, and the foul odors from the cells that now reached as far as the courtyard forced the Republic to find a solution by building New Prisons alongside the Palace.

The Prisons were accessible via the Bridge of Sighs, so after being tried inside the Doge’s Palace, inmates could reach the prisons directly without having to be led outside.

This was one of the first buildings in Europe created and designed to be a place of detention, designed by Antonio Rusconi in 1563 and completed by Antonio da Ponte.

The spacious building with massive and severe appearances was meant to provide the prisoners with healthier spaces with natural lighting and ventilation. It could hold up to 400 inmates.

The new two-story building is completely insulated on all four sides and features a large inner courtyard. Every window is equipped with strong bars to prevent inmates from escaping.

The main facade on the Schiavoni shore consists in the basement strip of a seven-arched Istrian stone portico of giant order with square pillars. The second floor has tall, slender openings with arched, triangular gables interspersed with Doric half-columns, in axis with the arches below.

The plan is crowned at the top by a corbelled cornice.

The façade placed in front of the Ducal Palace, on the Rio di Palazzo, has three orders of small, square openings; the vanishing lines of the bands of the ashlar walls in Istrian stone emphasize the perspective toward the Canonica’s Bridge.

Inside, along with the holding cells, was the room of the Magistracy of the Lords of the Night at Criminal. This body consisted of six members, one from each neighborhood of Venice, with the task of overseeing and instituting trials.

Their name was derived from the initial task of overseeing everything that happened in the city during the night. Members also met inside the torture room of the Doge’s Palace to attend interrogations.

The New Prisons would remain in operation until 1919, surviving the Republic of Venice, the French and Austrian dominations, and to some extent the Kingdom of Italy.

Visit to the Doge’s Palace and Prisons Venice: tickets for the Doge’s Secret Itineraries

Purchase online. Choose your preferred time. Visit Venice’s Doge’s Palace, Bridge of Sighs, prisons and more. You can cancel for free up to the day before your visit.

Frequently asked questions

How to see the prisons in Venice?

You can visit the prisons of the Doge’s Palace in Venice by purchasing “Secret Itineraries of the Doge’s Palace” tickets.

The visit begins with a small staircase downhill that leads from the Hall of the Magistrate of Laws into one of the two narrow corridors of the Bridge of Sighs. The tour will take you to the rooms where, in the centuries of the Venetian Republic, activities related to the administration of the state and the exercise of power and justice took place.

In which rooms was justice administered inside the Doge’s Palace of Venice?

Within the Palace justice was administered and all judicial, civil and criminal proceedings took place, the different magistracies were based in certain rooms of the Doge’s Palace, here is a list of the most important ones:

- Hall of the Inquisitors: this office, which arose in the year 1539, judged crimes that endangered the security of the Republic, illicit dealings with foreign emissaries, slander on the government and political faults. The ceiling of the room houses decorations by Tintoretto, evoking the principles that the judges had to respect when passing their sentences: The Faith, Justice, The Law and Concord, while in the center of the octagon is painted the return of the prodigal son, representing the purpose of the inquisitors’ deliberations.

- Hall of the Three Chiefs: In this hall sat the three presidents of the Council of Ten, who held office for a month and were tasked with hearing the accused by investigating the veracity of the facts, bringing the trials before the assembly, and informing the decemvirs and the Signoria on the most urgent measures. Inside the room are Giambattista Zelotti’s canvases, Virtue Liberates Time, Truth and Innocence from Evil and Envy, and Giambattista Ponchino’s monochrome canvases, Justice Overcomes Rebellion and Faith Prevails over Heresy. Finally, Paolo Veronese’s canvas Virtue Defeats Evil and Nemesis Triumphs over Sin.

- Hall of the Quarantia Civil Vecchia: The Quarantia was the highest appellate body of the Venetian state. It was originally a single body consisting of forty members with broad powers, political and legislative. Later the quarantie became three: Quarantia Criminal (for judgments in the area we would now call criminal), Quarantia Civil Vecchia (for civil cases on Venetian territory), Quarantia Civil Nuova (for civil cases on the mainland).

- Halls of the Quarantia Criminale and dei Cuoi: Older than the Quarantia Civile, the Quarantia Criminale held judicial power by ruling in an appellate capacity on criminal cases; it was governed by three heads who composed, together with the doge and his advisors, the Serenissima Signoria. The furnishings and decorations were completely removed after the fall of the Republic, except for the seventeenth-century wooden stalls.

- Hall of the Magistrate of Laws: Inside this hall the three conservators and enforcers of the laws and orders of the offices of St. Mark’s and Rialto carried out their duties; their task was to oversee compliance with the laws inherent in lawyering and arbitrate in cases between close relatives in testamentary cases. This was also where the College of Twenty Savi of the Body of Forty met, whose role it was to arbitrate in disputes involving sums of little importance. The walls are home to significant works of Flemish art, including the Hell signed by monogrammer J.S., Metsys’ Christ Mocked, and two signed triptychs by Hieronymus Bosch, formerly housed in the Hall of the Three Heads of the Council of Ten, the Triptych of the Hermit Saints and the Triptych of St. Julia.

- Hall of the Censors: this was where the two-member magistracy met, whose job was to oversee the fairness of voting, servants’ wages, betting, offenses committed by gondoliers, and offenses committed by glassmakers.

- Hall of the Avogadori di Comun: this magistracy supervised offenses concerning the commune’s property and adjudicated cases between the treasury and private individuals. It also had the power to oppose the deliberations of the Great Council, the Senato and the Council of Ten (whose meetings always had to be attended by at least one avogadore).

- Casket Hall: In this room the avogadors kept the register of all Venetian patrician families, the so-called “Gold Book”, in which conjugal unions and births were recorded, so as to oversee the regularity and legitimacy of the entry of young nobles into the Great Council. There was also a similar list called the ‘Silver Book’ for citizens called originals, a social class that enjoyed special privileges, such as those d trade with foreign countries and hold public administration positions.

- Hall of the Provveditori alla Milizia da Mar: this office was in charge of arming the galleys of the Venetian fleet and hired sailors. The trade guilds of Venice and the subject cities were required to provide a certain number of sailors, following the payment of a tax earmarked for this purpose.

- Lower Chancery Hall: this is where the college of notaries used to meet; today the hall is occupied by the bookshop.

- Hall of the Ducal Bull: this was the room where the bollador affixed the ducal bull of nihil obstat to all practices, giving them validity.

Prisons of the Doges’ Palace: conclusions

Here we are at the end of this article on the prisons of the ancient Venetian Republic, in which we discovered together what the Piombi and the Pozzi are, how prisoners were treated, where they were locked up, and how they, in some, escaped.

If you have any questions and would like further insights, please feel free to leave a comment below.

Visit to the Doge’s Palace and Prisons Venice: tickets for the Doge’s Secret Itineraries

Purchase online. Choose your preferred time. Visit Venice’s Doge’s Palace, Bridge of Sighs, prisons and more. You can cancel for free up to the day before your visit.

Photo credits:

- Cutaway of the prisons of the Doge’s Palace Venice: Photo via Wikimedia

- New Prisons of the Doge’s Palace Venice: Photo by Shay Tressa DeSimone via Flickr

- Piombi: Photo by di bart.lambert via Flickr