Have you decided to visit the Doge’s Palace in Venice but don’t know what this marvel of Italian artistic heritage has to offer?

You’ve come to the right place! I am Paolo from the Doge’s Palace Venice, and in this post I will tell you about the visit and special itineraries of the Doge’s Palace, also known as the Doge’s Palace, a monument that is a symbol of Venice and Italy.

Here I will explain the route of the visit that you can take on your own or by following a professional guide.

Are you ready? Let’s get started!

Before we start, a brief preamble: if you plan to visit the Doge’s Palace in Venice, (either by guided tour or on your own) it is strongly recommended to buy your ticket online, to avoid the long queue that may form at the ticket office. By purchasing the ticket in advance, you will be able to access the Palace by skipping the queue at the entrance.

Doge’s Palace Venice skip-the-line ticket: quick access

Buy online. Choose your preferred time. Visit Venice’s Doge’s Palace, Bridge of Sighs, prisons and more.

You can cancel for free up to the day before your visit.

Table of content

Visit the Doge’s Palace: the route in brief

Looking at the Doge’s Palace, or Palazzo del Doge, you will notice that it consists of four wings extending around the central porticoed courtyard. In height, however, it has three floors (the loggia, first and second noble floors) in addition to the prison building, which is external and accessible via the Bridge of Sighs between the first and second floors. In this context, you do not follow a linear route but find yourself going up and down the floors in stages.

To enter the Palace, you have to go to the Porta del Frumento – South Wing, overlooking St Mark’s Basin – from which you access the large porticoed courtyard.

Here, you can admire the two wellhead buildings, the majestic Giants’ Staircase and the clock façade of the Renaissance wing.

This floor is also home to the Opera Museum, where you can discover the ancient capitals of the Palace, replaced and displayed here following a renovation in the 19th century. To continue your visit, cross the courtyard to the west wing and take the Censors’ Staircase leading to the upper floors.

A short passage to the first floor, called the Piano delle Logge, will allow you to stroll through the loggia and admire the large inner courtyard from above. From here, continue following the signs to access the sumptuous Golden Staircase leading to the first and second piano noble.

On the first piano noble is the Doge’s Apartment located in the west wing. Here you can walk through the state rooms and learn more about the figure of the Doge through the works on display. Exhibitions and temporary exhibitions are also held in these rooms.

The last flight of the Golden Staircase will take you to the second piano noble (top floor) where you will visit the first part of the Institutional Chambers. On this floor is the Sala delle Quattro Porte (Hall of the Four Doors), named after its four finely ornamented marble doors, and the Sala del Senato (Senate Hall), where the senators whose job it was to control Venice’s finances and foreign policy gathered.

On the same floor, you can continue to the Armory, a former weapons depot divided into four rooms, which today displays more than two thousand pieces of weapons, armor and even instruments of torture.

After leaving the armory, descend back to the first floor through the Censors’ Staircase to visit the second group of institutional rooms.

On this floor the Halls also extend to the south wing, almost entirely occupied by the majestic Great Council Chamber, and to the west wing with the Scrutiny Room.

These rooms are the largest in the Palace:

- the first hosted the meetings of the Great Council, the highest political order of the Venetian Republic, chaired by the Doge;

- the second, originally used as a bookshop, later became the place for counting elections.

The exploration of the first piano noble ends in the Sala del Magistrato delle Leggi (Hall of the Magistrate of Laws): from here you descend via the small staircase to the famous Bridge of Sighs.

Cross the bridge and you will arrive at the New Prisons, located in a separate building on the other side of the Rio di Palazzo. In the building, erected in the second half of the 16th century, you will be able to see the former prisoners’ places of detention.

Retracing the Bridge of Sighs – via a second walkway – return to the Piano delle Logge to visit the last institutional rooms. From the last room, the Sala Milizia del Mar, you will finally reach the Bookshop.

At the end of the visit, descend back down to the courtyard to arrive in the 16th-century Senators’ Courtyard – where they gathered to await government meetings – to the right of the Giants’ Staircase.

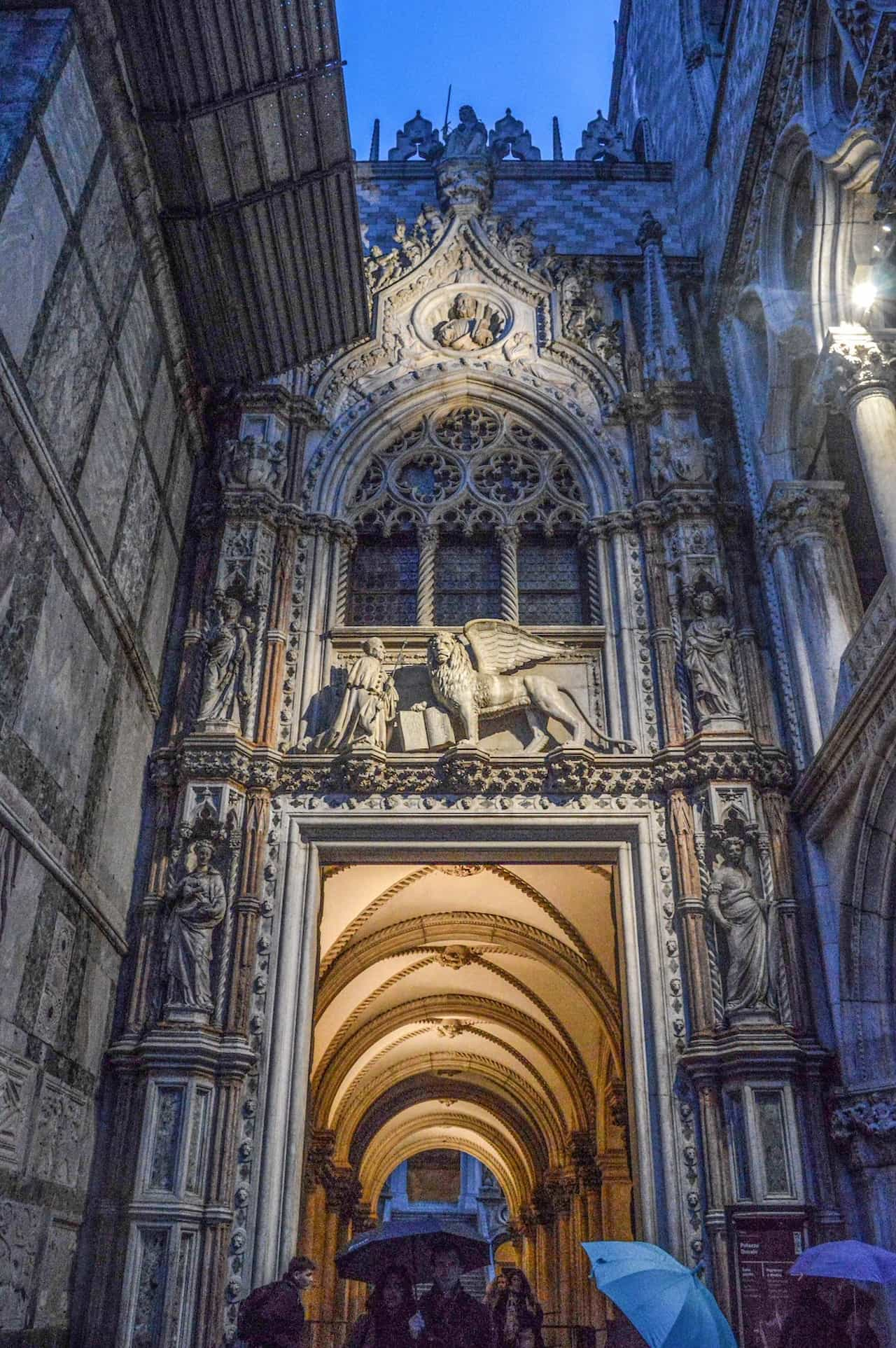

From here, passing under the Renaissance Arco Foscari, you can finally reach the exit of the palace through the monumental Paper door, which I recommend you observe carefully from the outside to admire its magnificence.

The tour is free, but guided tours are also organized.

In addition, you can visit the Museum at night (times vary according to the season) to get a unique and evocative perspective of the Palace and the works inside.

Doge’s Palace Venice skip-the-line ticket: quick access

Buy online. Choose your preferred time. Visit Venice’s Doge’s Palace, Bridge of Sighs, prisons and more.

You can cancel for free up to the day before your visit.

Venice Doge’s Palace self-guided tour

In this section we discuss the visit route in detail. You can follow this guide as an indication for a visit on your own, or as an anticipation for a visit together with a professional tour guide.

We begin our tour of the Doge’s Palace from the wonderful courtyard.

Courtyard

To enter the Museum you will have to pass through the 14th-century south wing, which overlooks the Bacino di San Marco, and go through the Porta del Frumento, named after the Ufficio delle Biade that once stood nearby. Pass the ticket office and enter the courtyard to begin your visit!

Interior facades

Inside, on the left side is the wing facing Piazzetta San Marco to the west, on the right side is the Renaissance wing to the east, and finally the courtyard is closed off by a fourth side to the north, where the Doge’s Palace borders St Mark’s Basilica, which was once the Doge’s chapel.

If you look around, you will notice that the southern and western interior brick façades retain the characteristic Venetian Gothic look of the corresponding exterior façades.

The eastern façade of the courtyard, on the other hand, is decorated with Renaissance marble and was designed by architect Antonio Rizzo after the radical reconstruction of the wing following the devastating fire of 1483.

Arco Foscari and the Paper door

By continuing the tour of the Doge’s Palace, on the north side is the Porticato or Arco Foscari: a round arch made of white Istrian stone and red Verona marble.

If you look up, you will notice a large clock at the top of the façade, the work of the German watchmaker Johan Slim, who made it in 1614 with a mechanism made of weights that reached down to the foundations of the palace and touched the water of an underground canal.

The Arco Foscari connects the inner courtyard to the majestic Paper door: once the main entrance to the palace, now the museum’s exit.

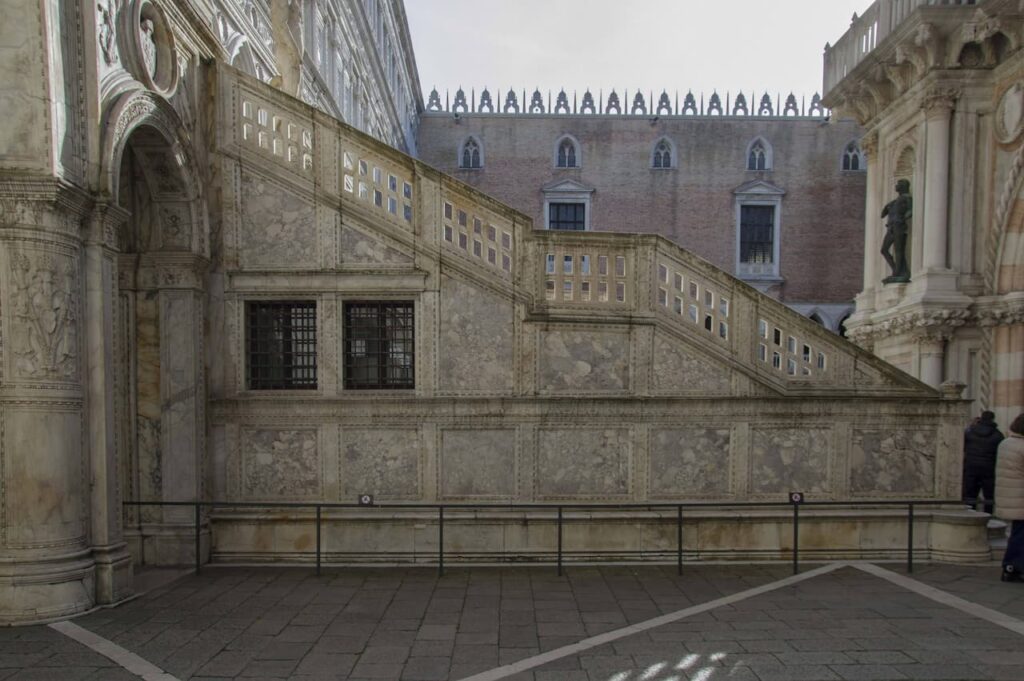

The Giants’ Staircase and the Senators’ Courtyard

As you stroll through the courtyard, you will see two massive and ornate bronze well-casters from the mid-16th century in the center and the imposing Giants’ Staircase: a natural extension of the Arco Foscari and the ancient entrance to the upper floors, it houses at its summit the statues of Mars and Neptune, sculpted by Sansovino in 1565, symbolizing the power of Venice.

To the right of the Giants’ Staircase you will find the 16th-century Senators’ Courtyard, where senators used to gather for government meetings.

The Censors’ Staircase

Also on the same side, but in the opposite direction to the majestic staircase, stands the Scala dei Censori under the elegant portico. This was built in 1525 to an architectural design by Antonio Abbondi, known as Scarpagnino.

Just by climbing the Censors’ Staircase you can continue your visit to the upper floors and immerse yourself in the rich artistic and historical heritage offered by the Doge’s Palace.

Opera Museum

The Opera Museum housed a technical office responsible for the maintenance of the building, located in the south-west corner of the ground floor.

In the 19th century, the Doge’s Palace was in a terrible state of disrepair, so it was decided to carry out a major intervention in 1876. A major restoration project was initiated in which 42 capitals of the exterior colonnade and other architectural elements were removed from the palace’s outer walls and courtyard and replaced with replicas.

The originals were restored and housed in the Opera Museum.

The capitals in the Museo dell’Opera are a precious and important part of the extraordinary sculptural apparatus that enriches the medieval facades of the Doge’s Palace. It is not just a simple decorative apparatus, but an articulate allegorical, religious, moral and political cycle that was certainly easier for a 14th and 15th century citizen to understand than it is today.

The sculptures on the capitals represent a veritable poem in stone, peopled by women, men, children, animals, plants, zodiac signs, myths, symbols, vices, virtues, grouped in tales, parables and demonstrations, allegories and moral foundations, along a path that, in a typically medieval process, combined history and legend, astronomy and astrology, the sacred and the profane.

The Opera Museum offers an itinerary based on this tale in stone and is currently divided into six rooms.

Hall I

This room contains six capitals and their columns from the 14th century portico of the palace overlooking St. Mark’s Basin. These are the oldest in the building, which was begun in 1340.

The first one you meet on your way, on the right, represents Solomon and the seven scholars.

Hall II

Unlike the capitals in the previous room, the four capitals in this room, with their columns, were originally located on the façade facing the Piazzetta.

The reliefs, of great sculptural quality, are very rich in allegories and moral teachings, dealing with topics related to work, the fruits of the earth, astrological correspondences, etc. On the entrance wall is a late 16th-century infill of one of the arches of the portico overlooking Ponte Paglia.

After the great fire that broke out in 1577, it was decided to plug the last arches for structural reasons.

Hall III

This room houses three capitals with columns. The first on the right, described by Ruskin as ‘the most beautiful in Europe’, was located in the corner between the square and the pier, under the sculptural group of Adam and Eve.

Approach the sculpture of The Creation of Adam, the planets and their houses: it is from this position that one can appreciate the importance of this sculptural group in the great iconographic program of the Palace.

The reading begins with the creation of the first man, visible on the left with his back to the entrance, and continues with the depiction of the planets and corresponding constellations. The image of God seated on a throne has just completed the formation of Adam, followed by the elderly and bearded Saturn, seated in Capricorn, with his precious Aquarian vessel, counterclockwise.

His attribute, the sickle, is still visible, making him the protector of work in the fields and reminding the government of his old age and death; next to it, Jupiter, with a cloak around his neck and a doctor’s hat, touches the sign of Pisces and sits above Sagittarius, armed with a bow and arrow.

Mars sits in Aries, flanked by Scorpio, like an armored warrior with sword and shield. A beautiful young man with his head covered in rays of light occupies the fifth floor. The Sun sits in Leo, holding a star in his left hand.

Venus is elegantly dressed with a belt across her chest, sitting in Taurus with Libra in her arms, admiring her beauty in the mirror. Next to her is Mercury, dressed in a toga and holding an open book. It is located between Virgo and Gemini.

Finally, the Virgin is placed on a boat, lifting the Moon’s hawk and touching the crab, symbol of Cancer. The boat and the canopy, moved by the wind, recall the Moon’s influence on the tides and the wind. At the end of the room, the last capital represents the deadly sins.

Moving away from the entrance and proceeding counter-clockwise, we find Pride, in the form of a warrior armed with sword and shield and wearing Satan’s horned helmet; Wrath, an old man tearing his clothes and cursing the heavens; Avarice, closing two bags with his fists; and Sloth, trapped between the branches in a lazy, passive posture. The next page depicts ‘vanity‘, which is not included in the seven main vices.

She is depicted as a maiden, her head adorned with flowers. She looks at herself in a mirror placed in her lap and touches her breasts. The jealousy that follows shows that she is aware that she is no longer an object of desire for others and is tormented by anger. The serpent above her head and the dragon grasping her breasts emphasize her demonic appearance. Desire exposes her breasts in the mirror and finally her throat lifts the glass and brings her thighs to her mouth.

Hall IV

In this room are two porch shafts and a massive stone wall with large rough-hewn and juxtaposed boulders, dating from an earlier phase of the building.

Hall V

Along the wall of the entrance are two other columns of the portico, while the one on the adjacent wall, with the foliate capital, belongs to the loggia of the façade facing the Piazzetta; a part of the gallery of the loggia was also placed in this room, with its succession of capitals resting on the pointed arches that give life to the quadrilobe surmounted by the rosette cornice. In the wedges of the arches are lion heads.

Hall VI

There are 29 loggia capitals in this room.

Turning back along the right wall, one comes across a bust. This is all that remains of the group depicting Doge Cristoforo Moro with the Marcian Lion, which was placed in the niche in front of the Scala dei Giganti, demolished during the fall of the Venetian Republic in 1797.

At the same end, the group with Doge Francesco Foscari kneeling in front of Bartolomeo Bon’s Lion above the Paper door, of which only the Doge’s head can be seen on the same side, goes towards the exit.

The group currently on the Paper door is a copy made in 1885.

Loggias Floor

From the floor of the loggias, the route begins along the three wings east, south and west of the palace, with fascinating views of the courtyard and Piazzetta San Marco.

It is precisely the loggias that give the palace’s architecture that characteristic lightness effect.

Today, the loggia floor houses the offices of the Soprintendenza per i Beni Ambientali e Architettonici di Venezia (Venice’s Environmental and Architectural Heritage Office) and some of the offices of the palace management, the Venetian Civic Museums, as well as one of the museum’s bookshops.

Doge’s Palace Venice skip-the-line ticket: quick access

Buy online. Choose your preferred time. Visit Venice’s Doge’s Palace, Bridge of Sighs, prisons and more.

You can cancel for free up to the day before your visit.

Doge’s Apartments

In 1556, as a continuation of the Giants’ Staircase, Doge Lorenzo Priuli gave Jacopo Sansovino the task of designing a staircase leading to his flats and state rooms.

The staircase was called the ‘Golden Staircase‘ because of the preciousness of the stuccoes covered in gold leaf and the fresco panels decorating the vault of the staircase.

At the top of the first ramp are two further ramps, one to the west and one to the east, both leading to the Doge’s Apartment on the First Noble Floor. The staircase served as a separation between the area of the Palace reserved for institutional functions and the Doge’s private area.

The Doge’s Apartment was located in the northern part of the Renaissance wing and ran between the mezzanines and hidden rooms, such as the antichiesetta and the chapel, which are not visible on the standard tour (Special Routes).

In 1505, the small Church of St Nicholas by Giorgio Spavento was built to close off the courtyard on the north side.

Today, the flats house a permanent exhibition dedicated to the figure of the doge and the city of Venice.

Institutional Chambers (Part I)

The tour of the institutional halls begins on the third floor of the palace. All you have to do is walk down the Golden Staircase and you will find yourself in the first room of the tour.

Square Atrium

The last step of the golden staircase leads to the square atrium.

This room leads to the hall where the most important meetings of the political life of the Venetian Republic took place.

In the center of the ceiling, Doge Girolamo Priuli (1559-1567), the eponymous saint and the symbols of peace and justice are depicted on an octagonal canvas by Tintoretto.

Eight side paintings with putti symbolizing biblical episodes and seasons were also painted by Tintoretto’s workshop. Currently on display are sacred scenes painted in the second half of the 16th century: the ‘Annunciation to the Shepherds’ by Girolamo Bassano and three canvases attributed to Veronese: ‘Adam and Eve Driven from Paradise’, ‘Prayer in the Garden’ and ‘St. John Writing the Apocalypse’.

Hall of the Four Doors

The Hall of the Four Gates was a solemn hall that filled the entire width of the floor, from the courtyard to the Rio. This hall served as a place for high-ranking representatives waiting to be admitted to the Council and as a link between the halls where the highest executive offices of the Republic met.

After a fire in 1574, it was restored according to plans by Andrea Palladio and Giovanni Antonio Rusconi. The barrel vault is decorated with gold and stucco work by Giovanni Battista Cambi, known as Bombarda.

The iconographic program of the ceiling is the work of the polyglot Francesco Sansovino.

Above the vault are allegorical figures, gods, putti, winged spirits, sirens, tritons and other grotesques.

The frescoes by Jacopo Tintoretto, of which little remains because they had to be restored due to weather and humidity problems, emphasize the strong symbolism.

The canvas, elliptical in shape, shows the personification of Venice and its subordinate cities (Verona, Brescia, Istria, Padua, Friuli, Treviso, Vicenza and Altino), with broad strokes depicting Jupiter ceding control of the Adriatic to Venice, Juno bestowing Venice with the insignia of power, and Venice removing the yoke of slavery.

There are canvases by Giambattista Tiepolo, Neptune Offering a Gift to Venice, made in 1758, and Venice Leaning on the World, by Niccolò Bambini.

Each of the four doors designed by Andrea Palladio features a sculptural group that recalls the activity of the governing body of the hall accessed:

- Vigilance, Eloquence, Ease of Hearing for the College

- Peace, Pallas, War for the Senate

- Authority, Religion, Justice for the Council of Ten

- Secrecy, Diligence, Loyalty for the Chancellery.

The decorations on the walls include votive scenes and re-enactments of historical events.

Antichamber of College

The Antichamber of College was the antechamber of honor where foreign delegations, Venetian ambassadors and magistrates returned from their duties to be received by the Serenissima Signoria.

This room was also damaged by fire in 1574 and was restored according to plans by Palladio and Vincenzo Scamozzi. On the pedestal above the monumental fireplace with the two marble telamons is a relief of Venus asking Vulcan for weapons for Aeneas.

The same technique is used for the wall and ceiling decorations, made by Marco D’Agnolo in 1576-77. In the centre of the ceiling is an image of Venus asking Vulcan for weapons for Aeneas.

In the centre of the ceiling is an octagon frescoed by Paolo Veronese depicting the distribution of wealth and honours by Venice.

On the walls are four mythological canvases by Jacopo Tintoretto, originally made for the square atrium: Mercury and the goddesses, Pallas driving out Mars, Arianus being picked up by Bacchus and The Forge of Vulcan. The allegories of these seasons can be interpreted as signifying the wise and reflective politics of the Republic.

Above the tympanum of the portal leading to the College Hall are three sculptures by Alessandro Vittoria personifying Venice, Concordia and Glory.

Senate Hall

The Senate, also called the Council of Pregates, consisted of a committee of 60 nobles and an equal number of nobles called Zonta.

During the meetings, the Senate was joined by the Small Council, the Quarantia, the Avogadori di Comun, the Council of Ten, the Saviours and, if necessary, other magistrates, making a total of 200 members.

This room was also restored by Antonio da Ponte after the fire.

The ceiling is wooden, with a central painting of the Triumph of Venice by Domenico Tintoretto, surrounded by various autographs depicting the virtues of the Republic.

The walls of the hall are decorated with two clocks, one of which depicts the twelve signs of the zodiac, allegorical scenes and votive paintings from the late 16th century.

Above the courtyard is a painting by Jacopo Tintoretto and Officina della morte di Cristo, supported by angels worshipped by Abbots Pietro Lando and Marcantonio Trevisan, and the triumphal return of Christ by Parma the Younger to Abbots Lorenzo and Girolamo Priuli.

Other paintings in this room are by Tintoretto, Parma the Younger, Tiepolo and Marco Vecellio.

Hall of the Council of Ten

This room housed a committee of ten, a small council and a commission consisting of at least one avogador from the comun.

Secret meetings were held here on sensitive issues such as national tranquility and prosperity, public order and morality, the punishment of crimes committed by political prisoners and nobles, and the morals and manners of citizens.

To achieve its goals, the commission could also resort to torture.

There are wooden bumps around the room where the deputies sat, but the bumps on the semicircular platform are missing.

A door led to the office behind and, via a staircase, to the prison.

The walls are painted with putti, allegorical figures and the coat-of-arms of Doge Francesco Dona on a frieze by Giambattista Zelotti, the Adoration of the Three Doctors by Antonio Ariense and the Peace of Bologna between Charles V and Clement VII from 1530 by Marco Vecellio, canvases from the late 16th and early 17th century adorn the walls.

They are by Giambattista Poncino da Castelfranco and Paolo Veronese. A series of chiaroscuro paintings with allegorical and symbolic subjects surround large panels depicting the gods and greatness of the Republic.

Compass Hall

The name of this room comes from the compass door in the corner of the room. The compass leads to two hidden passages above the statue of Justice.

From here, witnesses, lawyers and defendants could enter and leave the room where the trials of the three heads of the Supreme Court of the Republic, the Council of Ten and the Magistrate’s Court took place.

The place where the magistrate’s organs sat was connected to the old prison by a staircase that ascended from the well to the ponds.

In the center of the ceiling is a canvas depicting St. Mark Crowned with the Theological Virtues, a 19th-century copy of Paolo Veronese’s original, now in the Louvre after it was stolen by the French in 1797.

Armory

Down two flights of stairs you will find yourself inside the armory.

The armory collection consists of four rooms and includes more than two thousand weapons for the most diverse uses.

The first exhibition room, called the ‘Gattamelata Room’ after the armor of the condottiere Erasmo da Narni, known as Gattamelata, contains profiles of horses and their armor from the 16th century. Also on display are models of swords from various epochs, a model of a crossbow, a typical painted leather tulkassi for storing arrows and a lantern from a Turkish ship taken from the enemy (with its characteristic crescent moon).

The second gallery is decorated with the triangular Turkish flag at the famous Battle of Lepanto in 1571. In the center is an inscription in honor of Allah and his prophet Muhammad, with a verse from the Koran embroidered on the border. Of particular note is the armor donated to the Republic by Henry IV of France during his visit in 1604. Also in this room are two ornate fire lances, several broadswords and a 15th century horse’s head armor.

Room III takes its name from the bust of Francesco Morosini in the back niche; during the war against the Turks from 1684 to 1688, the admiral was appointed supreme commander of the Venetian fleet and was given the honorary nickname Peloponnesian; in 1688 he became doge. This room contains numerous swords, pikes, arrowheads and crossbows, often inscribed or painted with CX’s initials. A culverin from the mid 16th century, a small decorated cannon and a 17th century arquebus with 20 barrels (10 long and 10 short) can also be seen in this room.

Various types of weapons are displayed in Room IV, including a 16th century fire crossbow, a fire club, an axe, a fire sword and an arquebus from the 17th century. Of interest are the so-called ‘Devil’s Box’, a trap that conceals poisoned arrows, four gun barrels that explode when opened and a trap. In this room are torture instruments, chastity belts and various weapons that were banned because they were small and easy to hide. They belonged to the Carrara family of Padua, exterminated by the Venetians in 1405.

Doge’s Palace Venice skip-the-line ticket: quick access

Buy online. Choose your preferred time. Visit Venice’s Doge’s Palace, Bridge of Sighs, prisons and more.

You can cancel for free up to the day before your visit.

Institutional Chambers (Part II)

From the armory, you will descend a few flights of stairs to the second floor of the palace to continue your tour of the institutional rooms.

Liagò

This room was used as an antechamber to the Great Council Hall.

The gilded beamed ceiling dates back to the 16th century and features works by Domenico Tintoretto (Governor Giovanni Bembo in front of Venice, depicting sailors, transformations and allegorical figures presenting a model of a galley in Santa Giustina), Jacopo Palma (in front of the Virgin with figures representing the city, religion and discord, Patriarch Marcantonio Memmo), among others.

On display in the adjacent vestibule are the sketch of the mosaic for the second external portal of St. Mark’s Basilica by Sebastiano Ricci (‘Arrival in Venice of the Body of St. Mark’) and three sculptures by Antonio Rizzo (‘Adam and Eve’, ‘The Shield Bearer’), intended to decorate the Foscari Arch.

Hall of the Quarantia Civil Vecchia

The room housed the Magistracy of the Council of Forty, which operated in judicial matters. In the 15th century, the Council was divided into three councils:

- The Criminal Quarantine for Criminal Offences

- The Quarantia Civil Vecchia for the Lawsuits and Appeals of the City Venice

- The Quarantia Civil Nuova for the Lawsuits and Appeals of the Mainland

The space, which took on its original conformation in the 17th century, is dominated by the large Gothic window on the side of the river, and preserves behind the wooden dossals on the perimeter, traces of a fresco from the previous decoration.

The 17th-century canvases depict themes related to the celebration of Venice.

Guariento Hall

This small room was used as an ammunition depot, as well as a resting place for the military corps that supervised the meetings of the Great Council.

The interior houses the large 14th-century fresco by Guariento, which was found under Tintoretto’s painting of Paradise, and then detached and relocated in 1903. The work represents the Coronation of the Virgin seated on a throne next to the Redeemer.

Great Council Hall

The wing of the Doge’s Palace facing St. Mark’s Basilica is almost entirely occupied by the Hall of the Great Council, where the Plenary Council of the Republic was held.

The Doge sat in the center of the hall with his councillors, surrounded by the three heads of the Council of Ten, the Quarantia Criminale, the Avogadori di Comun and the censors, while those entitled to vote sat on the side seats surrounding the hall and on the double seats in rows of nine.

The huge hall, measuring 53 meters long and 25 meters wide, could seat more than 2,000 people, occupying almost the entire wing of the palace facing St. Mark’s Basilica.

The wooden ceiling is completely covered with gilded and painted canvases, and its structure consists of a system of beams and trusses capable of supporting the heavy ceiling without the aid of columns.

The walls are covered with large canvases depicting episodes from the history of Venice, such as the Fourth Crusade in 1202 and The Peace of Venice, which concerns relations with the Papacy and the Holy Roman Empire.

The canvases that adorn the roof of the room depict the deeds and virtues of valiant Venetian citizens, while in the center is the Triumph of Venice Crowned with Victory, an allegorical eulogy of the Republic by Veronese. It depicts a Venice crowned with glory and surrounded by honor, peace and happiness, with the entire Venetian society, from the nobility to the people, protected by mounted guards.

Toward the courtyard are depicted twelve episodes relating to the events of Alexander III and Frederick Barbarossa.

Under the ceiling is a frieze by Tintoretto, with portraits of the first 76 doges of Venice (804-1556).

At the end of the room is a painting of “Paradise” painted by Jacopo Tintoretto between 1588 and 1592.

The painting features Jesus and Mary as protagonists, with the light descending on them and the Holy Spirit descending right on the tympanum of the throne on which the Doge sits.

The theme is not only religious, but also an allegory of good governance, of the light that enters the figure of the Doge and the divine essence that enables him to always make the right decision.

Scrutiny Hall

By trespassing through the corridors and adjoining rooms where the Quarantia Civil Nuova was opened, one arrives at the voting room.

Before being destined for this purpose, it housed precious manuscripts donated by Francesco Petrarca and Cardinal Bressanone to the Venetian Republic and later transferred to the Biblioteca Marciana.

The original works in this room were destroyed by fire in 1577. The new design was created by Cristoforo Forte.

The wall paintings depict the illustrious exploits of the citizens of Venice. Of particular note is the painting of the Last Judgement by Jacopo da Palma il Giovane (1594 – 1595).

The Picture Gallery

Starting in 1615, a nucleus of paintings owned by Cardinal Domenico Grimani, and acquired by the Venetian Republic after his death, was exhibited to the public in the rooms of the Doge’s Palace. The Flemish easel paintings, which had nothing to do with the history of the place, were soon permanently exhibited in the rooms of the Palace.

Marco Boschini, in his ‘Guide to Paintings‘ in Venice in 1664, mentions ’15 small paintings by Civetta (Heri de Bresse) in the path leading to the Council of Ten room, and a triptych of crucified saints, the Martyrdom of Santa Liberata, by Jeronymus Bosch’.

In 1773, Anton Maria Zanetti confirmed that the 15 paintings Boschini had seen a century earlier were in the palace.

Zanetti stated that these were eight landscapes in the antique style, a triptych and four compositions ‘with eccentric inventions’, which he attributed to Civetta, and which were exhibited in the Sala dei Tre Capi of the Council of X from 1771, together with the triptych of Santa Liberata.

In the 1770s, in an attempt to re-establish this tradition, a space was created in the hall of the Magistrate of Laws, together with the hall of the Three Chiefs, to display the original paintings existing in the palace, including the panels by Yeronymus Bosch, now in the Accademia Gallery in Venice.

The building was also used as the main exhibition space of the Palace.

The current layout of the Hall of the Criminal Quarantia, the Hall of the Hides and the Hall of the Magistrate of Laws was part of this tradition, where easel paintings from private collections were also exhibited, alongside decorative apparatus.

The Vision of the Apocalypse, the only Flemish work visible to the public in the palace after 1615, had previously been attributed to Owl, but is now attributed to an anonymous follower of Bosch.

Next to it is a 16th century Flemish painting by Maarten de Vos. Next to it are 16th century Flemish paintings by Maerten de Vos, Quentin Metsys and Frans Floris.

The other rooms display masterpieces by the best of Venetian art – Giovanni Bellini, Titian, Jacopo Tintoretto and Giambattista Tiepolo – Anthony van Dyck . The exhibition also includes works by the ‘heroine’ painter Artemisia Gentileschi.

Criminal Quarantia and Leather Hall

This room was one of the three Quarantia (the highest courts of appeal in the Venetian state); the Quarantia Criminal, founded in the 15th century, dealt with criminal decisions.

Its members were also members of the Senate, which also gave them legislative powers. The hall is decorated with wooden stalls dating back to the 17th century.

The next room was the archive of this judiciary.

It is assumed that the walls were lined with shelves and cupboards, of which the one on the back wall is an example. The gold-embroidered leather called ‘cuoridoro’ on the other walls is not original furniture.

Hall of the Magistrate of Laws

This room housed the authority of the administrators and enforcers of the laws and orders of the municipal offices of St. Mark’s and Rialto, created in 1553 and entrusted to three patricians whose task was to enforce the laws that regulated the legal profession.

In Venice, a pre-eminent commercial city, the judicial branch was of great importance (one thinks first of all of the enormous number of lawsuits, disputes and trials caused by the existence of such a vast market as the Rialto).

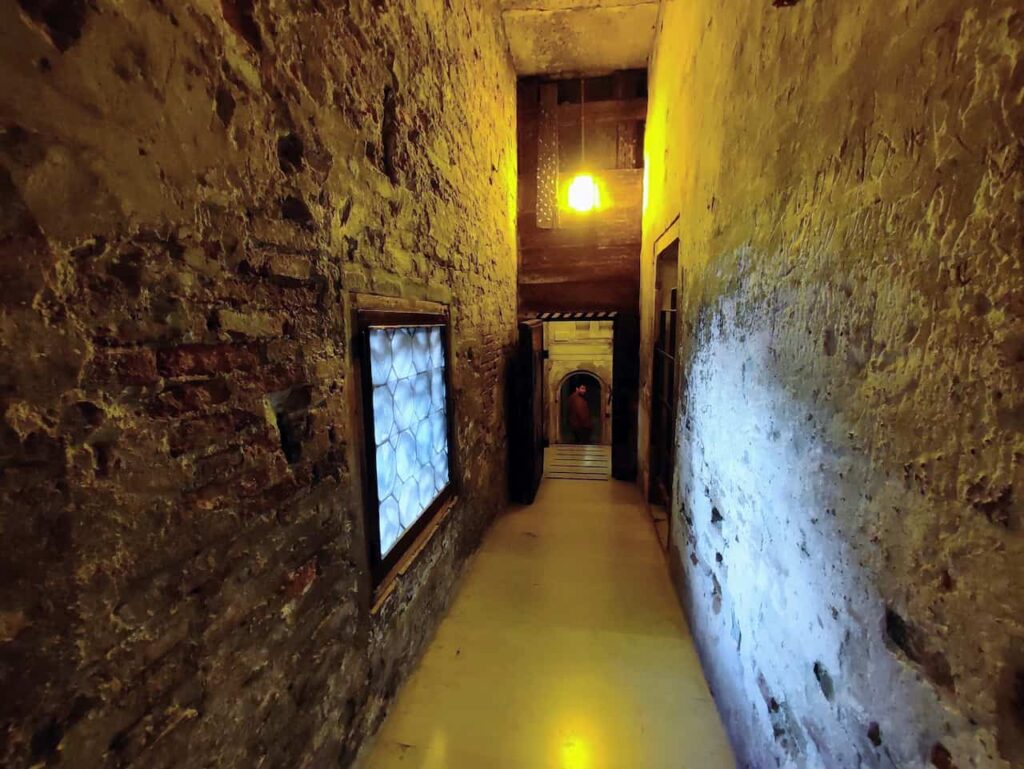

Bridge of Sighs and New Prisons

The construction of the bridge took place in the early 17th century, in conjunction with the renovation of the prison of the Doge’s Palace in Venice, which had been devastated by the great fire of 1577.

The interior consists of two narrow corridors separated by thick walls, the first leading to the Hall of the Magistracy and the second to the Hall of Avogadria and the Parlatory.

In 1602, Doge Marino Grimani commissioned the Swiss-Italian architect Antonio Contin, grandson of Antonio da Ponte, the architect who built the Rialto Bridge.

The plan was to build new prisons of modern design, on the opposite bank of the Rio di Palazzo, and to connect them to the Doge’s Palace by means of the bridge, designed as a completely closed suspended passage to prevent prisoners from escaping.

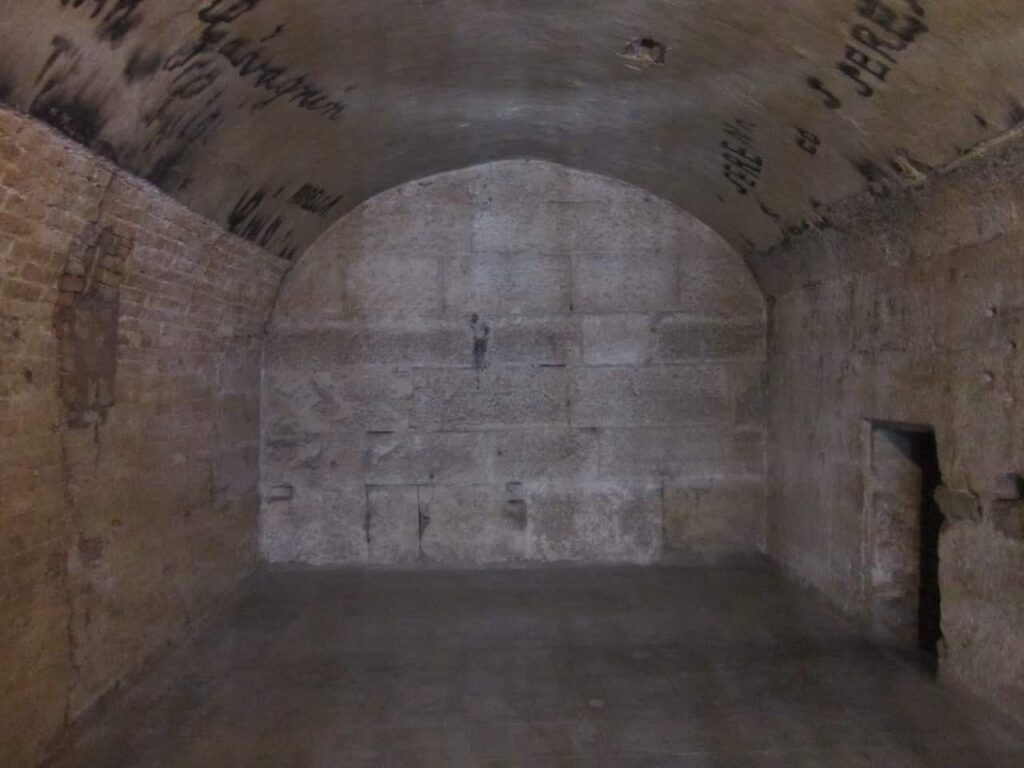

After crossing the Bridge of Sighs, you will find yourself directly inside the New Prisons, where you can observe the old prison cells of the building until you reach the inner courtyard.

The last room of the prisons displays archaeological finds with interesting examples of handicrafts, especially ceramics, from different eras, from Roman to modern times, collected during excavations carried out by the Venice Environmental and Architectural Heritage Office as part of the restoration of the historic center and the lagoon.

The oldest specimens come from the deepest part of the excavations carried out in 1902 in St. Mark’s Square after the collapse of the bell tower, where fragments of Roman, late antique and early medieval amphorae and numerous food remains (animal bones and mollusk shells) were found, as well as other more recent artefacts dating back to the 16th and 17th centuries.

Excavations in the church of San Lorenzo di Castello, on the other hand, yielded Byzantine and Middle Eastern vases from the 11th and 12th centuries, as well as locally produced common pottery from the 9th and 10th centuries and Middle Eastern ceramics from the 11th-12th centuries.

A large quantity of graffito ceramics was also found. Bowls, plates, basins and jugs; most of the material, estimated to date between the 14th and 16th centuries, comes from the excavations at Malamocco and from the National Archives in Venice (formerly the Frari Monastery), where a few shards of imported ceramics, in particular of Hispano-Moorish origin, were recovered in association with local pottery.

Findings from the restoration of the New Prisons and the restoration of the National Archives document the continuity and consistency of local manufacturing over the centuries until the early 19th century.

Doge’s Palace Venice skip-the-line ticket: quick access

Buy online. Choose your preferred time. Visit Venice’s Doge’s Palace, Bridge of Sighs, prisons and more.

You can cancel for free up to the day before your visit.

Institutional Halls (Part III)

After crossing the Bridge of Sighs and the New Prisons you will be taken back inside the Doge’s Palace, where you can complete your tour of the institutional rooms.

Hall of Censors

Here is a room dedicated to judicial bodies: the figure of the Censor was established in 1517 on the initiative of Marco Foscari di Giovanni, cousin of Doge Andrea Gritti (1523-1538) and nephew of the great Francesco Foscari.

In reality, the censor was not a judging body but a moral advisor. A series of paintings by Domenico Tintoretto depict various magistrates on the walls, with the coats of arms of those who held this office underneath.

Avogaria Hall

The Avogaria de Comun, as its name suggests, is a very old judicial institution, dating back to the Commune period (12th century), where the task of the three avogadors was to uphold the principle of legality, i.e. the correct application of the law.

Until the fall of the republic, it constituted, after the Council of Ten, the most authoritative administrative body for the defense of the law.

They also controlled the purity of the nobility, i.e. the legitimacy of noble marriages and births recorded in the Golden Book. In this room, the avogadors are depicted performing acts of devotion in the presence of the Virgin, the risen Christ and the saints.

Casket Room

The Venetian aristocracy originated from the ‘Serrata‘ of the Grand Council in 1297, but only later, at the beginning of the 16th century, was a set of rules decided upon to protect the nobility.

Marriages between nobles and people of different social classes were banned and checks to confirm the title of nobility were strengthened.

Thus, if someone did not formally notify themselves, they risked being excluded from the nobility and, consequently, from participation in the Grand Council and political activity.

Thereafter, all nobles, regardless of the social status of their wives, were obliged to present the marriage certificate to the avogaria.

In other words, in addition to the requirements of ‘civility’ and ‘honor’, these were people who could boast ancient Venetian origins, i.e. those who provided the state with a host of officials, including the ducal secretariat.

The gold book and the silver book were kept in the casket in this room. The one seen today, which occupies three sides of the niche, dates back to the 18th century and is lacquered white and decorated with gold.

Militia da Mar Hall

Established in the mid-16th century, this body consisted of about twenty members of the Senate and the Great Council and was responsible for recruiting crews for the war galleys.

This was not an easy task, given the numbers needed for the vast Venetian fleet.

This office was associated with a magistrate called proveditori all’armar, who was mainly in charge of the fitting out and dismantling of ships, i.e. the hull and provisions on board.

The furniture in the dossal hall dates back to the 16th century, while the torches on the walls date back to the 18th century.

The next room was the office of the Lower Chancellery. From here one could exit into the loggia, overlooking the Scala dei Giganti.

Special tours of the Doge’s Palace

Secret Itineraries

The ‘Secret Itineraries‘ guided tour includes, in addition to the canonical tour of the palace, described in the previous paragraphs, the guided tour inside the rooms used for the administration of justice in criminal cases. The name ‘secret’ alludes to the fact that these rooms are hidden in the palace, behind closed doors.

The tour starts from the prisons on the ground floor, then the visitor will be led through the ‘secret’ rooms of the Doge’s Palace where officials of the bureaucracy had their offices and where the supreme judicial body of the Council of Ten met, and finally the secret archive, where the most important state documents were kept.

The tour will take the visitor up to the attic where the upper cells, called Piombi, are located, in which political prisoners, sometimes foreigners, were locked up, including the famous Giacomo Casanova, who also managed to escape in 1757.

The tour will end in the square atrium hall, from where you can continue your tour of the palace on your own.

You can find out more about this visit by visiting the article on the Secret Itineraries of the Doge’s Palace Venice.

The Doge’s Hidden Treasures

This guided tour allows you to visit the private routes, secret rooms and passages reserved for the Doge, including the privilege of admiring St. Mark’s Square from the loggia from which the Doge contemplated between two red columns.

The tour starts at the Loggia Foscara, and from here a trained guide will take you to the Foscari arch terrace, the secret archive, the treasure room, and the doge’s private chapel.

The tour ends in the antichiesetta room, and from here you can resume the visit of the palace on your own.

Read on to discover the visit route in detail.

You can find out more about this visit by clicking on the button below.

Doge’s Palace tour Venice: FAQ

The average visit lasts two hours. However, it depends on how much you want to explore the different rooms and works, who you are travelling with, and how much time you have available. If you would like to know more, read the article on how long a visit to the Doge’s Palace Venice lasts.

If you would like to visit the Doge’s Palace on your own, you can purchase a ticket for the Doge’s Palace. If, on the other hand, you would like to visit the building together with a professional tour guide, you can purchase a ticket for a guided tour of the Doge’s Palace.

The full price ticket to the Doge’s Palace costs €30, the reduced one €16. For more information, read the article on the cost of tickets for the Doge’s Palace in Venice.

The standard ticket for the Doge’s Palace Venice includes a visit to the Doge’s Palace, the Correr Museum, the National Archaeological Museum and the Basilica Marciana.

Of course! You can follow the self-guided walking tour found in this article and visit the Doge’s Palace in Venice on your own.

Doge’s Palace self guided tour: conclusions

Here we are at the end of this long post on visiting the Doge’s Palace in Venice, in which I have listed in succession all the rooms you will be able to visit and the secret itineraries provided by the museum.

If you have any doubts or other questions, leave a comment below, I will be happy to answer you!

2 Comments. Leave new

After crossing the “Rialto” bridge? Do you mean the ponte di sospiri (Bridge of Sighs)?

Yes, Jones.

Andrea