Are you planning to visit the Doge’s Palace in Venice and want more information about guided tours? Today we will discover together one of the itineraries of the special tours that the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia has prepared for the most curious visitors: The Doge’s Hidden Treasures.

In this article you will find some technical information on the guided tour, and we will take a detailed look at the different destinations of the itinerary: all the rooms and the works inside.

The Doge’s Hidden Treasures: guided tour tickets.

Purchase online. Choose the time of your choice. Join the guided tour of the secret terraces and hidden treasures of the Doge’s Palace by skipping the queue at the ticket office.

You can cancel for free up to the day before the tour.

Table of content

- 1 The Doge’s Hidden Treasures: useful info

- 2 What is Hidden Doge’s Treasure Tour?

- 3 The “Doge’s Palace Hidden Treasures” Tour in detail

- 4 Doge’s Hidden Treasures: things to know before visiting

- 5 Doge’s Hidden Treasures Tour: tickets and reservations

- 6 Visiting the Hidden Treasures of the Doge’s Palace: frequently asked questions

- 7 Doge’s Hidden Treasures Tour: conclusions

The Doge’s Hidden Treasures: useful info

- Length of visit: 1.15 h

- Full price ticket: 38€ (the ticket includes the visit to the Doge’s Palace in addition to the guided tour).

- Reduced price ticket*: 26€ (the ticket includes, in addition to the guided tour, a visit to the Doge’s Palace). *Residents and those born in the Municipality of Venice; children from 6 to 14 years old; students from 15 to 25 years old with student card; citizens over 65 years old; RollingVenice Card holders; VeneziaUnica Pack holders; MuveFriend Card holders, purchasers of tickets for St Mark’s Square Museums, Museum Pass; Clock Tower ticket holders; I.C.O.M. members, staff of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities, ISIC – International Student Identity Card holders.

- Hours: 11 a.m. (English) – 1 p.m. (Italian) – 2.30 p.m. (French) – 4 p.m. (English).

- Language: Italian, English, French.

- Number of participants: from a minimum of 2 to a maximum of 10 people.

- Accessibility: The visit involves the use of several stairs, so unfortunately it is not accessible to people in wheelchairs or with mobility difficulties.

- Starting point of the visit: The visit starts near the gondola in the courtyard of the Doge’s Palace, from here the guide will take you along the route of the Doge’s Hidden Treasures.

- Ticket office: Click here to buy tickets.

What is Hidden Doge’s Treasure Tour?

This itinerary of the Doge’s Palace Hidden Treasure Tour, devised by curators Daniele D’Anza and Luigi Zanini, with the scientific coordination of Chiara Squarcina, will allow you to visit some of the rooms of the palace that are excluded from the ordinary Doge’s Palace tour.

Despite the name might suggest it, the guided tour does not allow you to visit riches such as gold or jewels, but rather private paths, secret rooms and passages reserved for the Doge, including the privilege of admiring St Mark’s Square from the loggia from which the Doge contemplated between two red columns.

The tour starts at the Loggia Foscara, and from here a trained guide will take you to the terrace of the Foscari arch, the secret archive, the treasure room, and the Doge’s private chapel.

The tour ends in the antichiesetta room, and from here you can resume the visit of the palace on your own.

Read on to discover the visit route in detail.

The Doge’s Palace Hidden Treasures tour: official online ticket

Purchase online. Choose the time of your choice. Join the guided tour of the secret terraces and hidden treasures of the Doge’s Palace by skipping the queue at the ticket office.

You can cancel for free up to the day before the tour.

The “Doge’s Palace Hidden Treasures” Tour in detail

We begin the guided tour of the Doge’s Hidden Treasures by climbing the grand staircase and arriving at the upper loggia, called Loggia Foscara.

Loggia Foscara

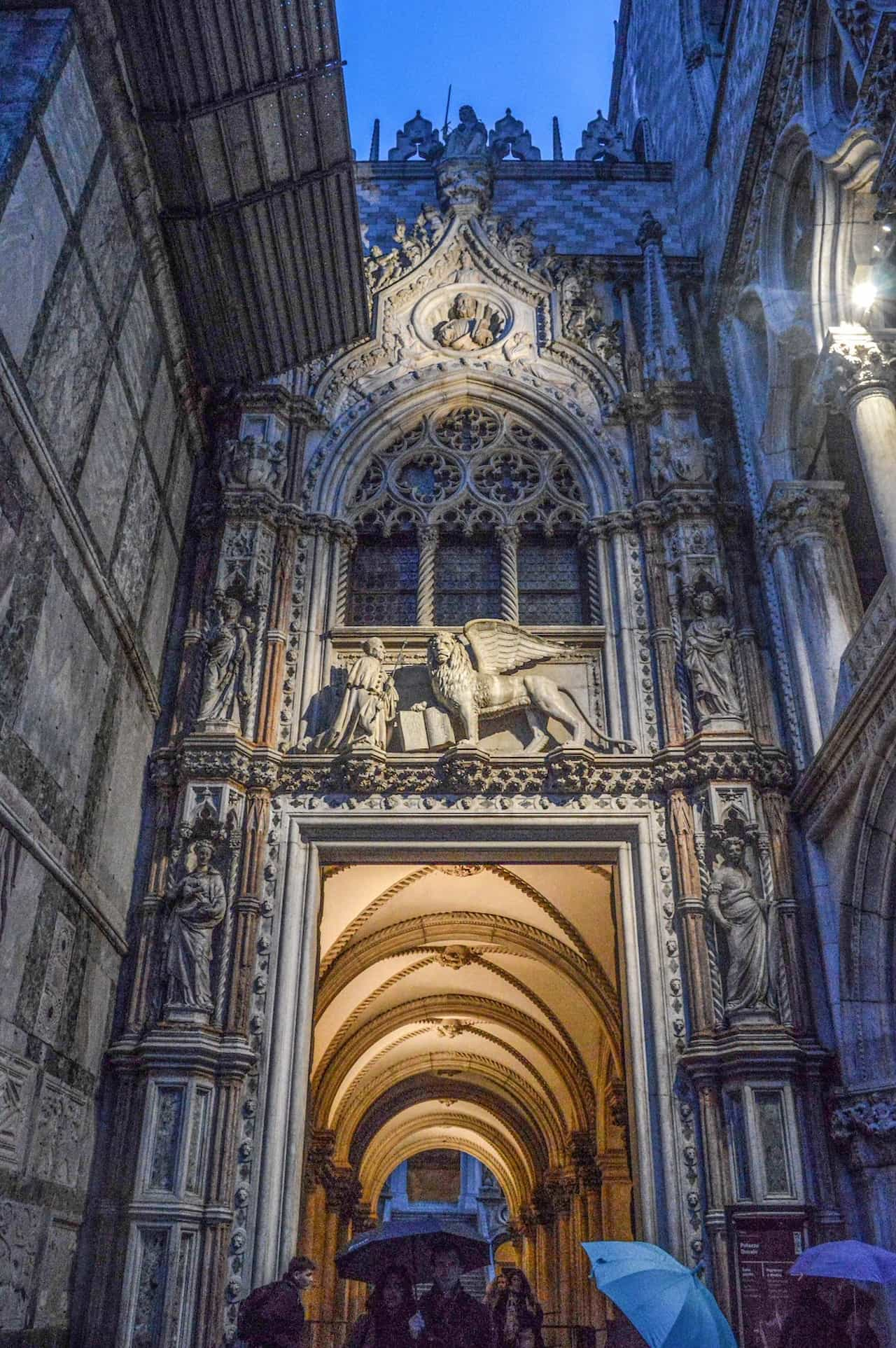

From the Foscara Loggia we can take a closer look at the Porta della Carta (Paper Door): laws were posted here and scribes welcomed visitors.

This, which today is the exit of the museum, was actually the main entrance to the Palace. In fact, until the late 16th century, the building was surrounded by the canal and this was its water gate.

This gateway was rebuilt in the 15th century at the behest of Doge Francesco Foscari, a very important doge elected quite young (48 years old), his tenure was the longest and one of the most successful in the history of the Republic. During his almost thirty-five years as doge, Venice went through a very prosperous period economically and many works in the palace were financed.

The doorway was designed and sculpted by Bartolomeo Bon and is one of the first works of art in the world to bear the author’s signature; you can see the inscription ”opus Bartolomeii”.

The door leaves you marvelling at its sculptures: the allegory of Justice at its top, the portrait of St Mark and Doge Francesco Foscari kneeling in front of the Winged Lion. The winged lion, which you will see several times in the palace, was the symbol of the evangelist St. Mark. The most accepted theory of historians is that the symbols of the evangelists represent the virtues of Christ most celebrated in the gospel, and the one represented by the lion is the fortitude, or strength, of Jesus.

The winged lion always holds between his paws the open book with the prophecy ‘pax tibi Marcae evangelista meus’. Legend has it that an angel appeared to St. Mark in Egypt and told him that he would find his peace on the island in the Venetian lagoon.

The doge is depicted kneeling; in Venice there was a law that the doge was always represented in this way when he was facing one of the symbols of religion or state, and the lion personified both. This was to remind the doge and other citizens that he was not a king, but someone serving the public interest.

The two pink columns, which you can see on the right as you look towards the lagoon, were mainly the place where a sort of throne was placed from which the doge watched the ceremonies taking place in the square. In fact, doges from 1355 were no longer allowed to leave the palace. It is also said that ordinary people were executed between the two columns of St. Mark’s and that noblemen were executed between the two red columns, but there is no historical certainty on this thesis.

The loggia was also built in the 1400s. On the portal is the figure of the doge who financed its construction, Francesco Foscari.

The Doge’s Hidden Treasures: guided tour tickets.

Purchase online. Choose the time of your choice. Join the guided tour of the secret terraces and hidden treasures of the Doge’s Palace by skipping the queue at the ticket office.

You can cancel for free up to the day before the tour.

Foscari Arch

You can see the Foscari arch, which was built for a purely structural reason. It is in fact a large buttress that helps to keep the side of St Mark’s Basilica, which is leaning against the Palace, in place.

This is not at all uncommon in Venice, which rests its heavy foundations on wooden piles driven into the ground of the lagoon.

The arch was initially used by the Doge to reach from his flats, located in the east wing, the west wing of the palace, where the Scrutiny Room is today and where until the end of the 16th century the great state library was located, moved in 1560 to the large Sansovinian library.

Initially, this space was an extension of the doge’s private quarters in the palace.

Then, starting in 1523, it was destined to house the archive of a new magistracy, the ‘Sora i Monasteri’, with the task of controlling what happened in the monasteries.

Archive of the Magistracy Sora i Monasteri

In 1523 Venice received an excommunication from the Pope (which was not the first) because of its financial management of monasteries and churches, including St Mark’s Basilica, the destination of many pilgrims.

In this case, the excommunication came because the management system of the monasteries was a little outside the rules.

In fact, there were a number of monasteries in Venice, only accessible to the daughters of very rich families, which over the centuries had turned into high-class schools.

Families who did not want to marry off their younger daughters, in order not to disperse the family inheritance, paid large fees to the monasteries to guarantee their girls a fairly normal life.

In addition, these ‘dowries’ devolved to the monasteries were managed by the Venetian government and not by the church, which also levied rather large taxes, a matter obviously frowned upon by the church.

The magistracy in charge of overseeing the monasteries rather than curbing this system concealed it better, since the Venetian government had every interest in fomenting it.

Thus, this part of the Foscari arch was used by the magistrates as their archive, given its isolated position in a corner of the palace. The documents could thus be kept in a secret and separate place from the rest of the archives.

The shelves that you can see today have been restored after many changes were made during the Habsburg rule in the mid-1800s.

The shelves retain their original structure and there are two secret passages; the more papers were hidden in the archive, the larger and more important the dowries were.

If you go through one of the passages you will come to a small room, which served as a guard post on the upper floors, in which there is now a suit of armour.

The armour belonged to the Contarini family, as can be recognised by the engraved coat of arms.

Precious armour such as this was not used in battle, but only for parades.

The Treasure Room

Going upstairs you will finally reach the Treasure Room. This room is filled with large chests, each of which was built here in the late 1600s, the structure is made of wood and covered with iron panels.

Each of these safes has a double system of locks, which could only be opened with large keys, and contained gold, precious objects, coins, and everything that was held by the dowries that were sent to the monasteries.

On display today are a number of precious objects that could have been found in this room in the past. The most precious objects are the glassware, showing different glassmaking techniques that the masters of Murano invented to copy other materials.

You can also observe instruments that were used by magistrates to vote. The magistrates used the famous ‘balotte’ system, all magistrates would take a ball, approach a box like the one in the showcase and leave their ball on top of the box.

They would then put their hand in the tube coming out of the box, turn the ring nut inside and decide whether to let the ball go on the green side or the red side. This system was used to keep the vote secret.

When everyone had finished, they would open the golden drawers at the sides of the box and take out all the balls, arranging them in another box like the one on the left side of the case.

Once they were arranged, it was no longer possible to touch them, and they were counted with the little golden hand that will surely have already caught your attention by looking at the photo.

Also preserved are ducal promise books, a very important document that was initialled at each new election of the doge. The doge was obliged to sign it after his election and during the ceremony of his first coronation with the ducal horn.

It was a list containing all the rules of conduct in public and private life, obligations etc. that the doge had to follow to avoid being deposed.

Doges could never leave office of their own free will, but could only be deposed by the Great Council, which was obviously one of the greatest possible dishonours for a Venetian nobleman.

This document would become more and more consistent over the course of the various dogates.

In 1355, after a further coup d’état engineered by the then Doge Marin Falier to establish a monarchy in place of the Republic, more than a hundred pages of new rules were added to the promissory note, including the rule that doges were no longer allowed to leave the palace.

The Giants’ Staircase

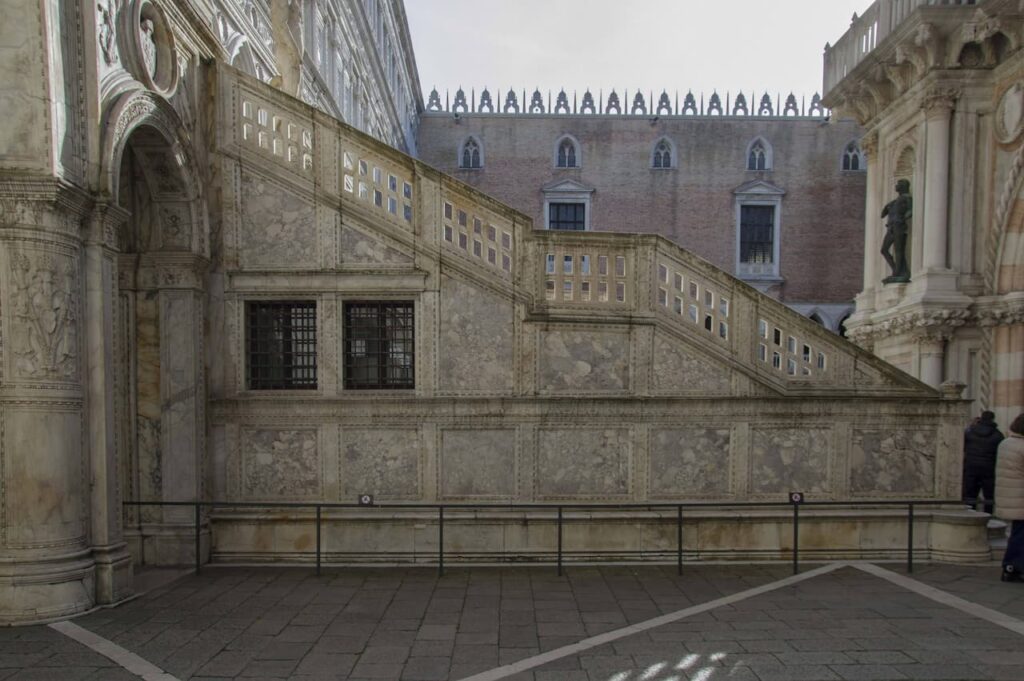

Exiting through the Foscaro arch again, the route takes you to the other side of the Porta della Carta, opposite the Giants’ Staircase.

This Staircase is a very important and symbolic place in the palace because this is where the doges were crowned for the first time after their election.

Before this staircase there was another one, this is the latest version designed by Antonio Rizzo, the same architect who designed the east façade of the Palace.

The new one was paid for by Doge Barbarigo, the staircase bears his characteristic coat of arms with six beards and a line (barba – line).

The staircase was so called because in 1565 the two statues by Jacopo Sansovino, Mars and Neptune, symbols of Venice’s power over sea and land, were placed there.

Above the staircase is the winged lion.

The ducal flats are on the very floor between the lion and the institutional rooms, for only one floor and only the northern part of the east wing, in a very small section of the palace.

We now ascend to the doge’s private terrace, connected to his flats.

The terrace backs onto the Basilica, whose Byzantine brick and Istrian stone structure dates back to 1003.

The fresco of St Christopher

Continuing the guided tour, ascending the stairs, and passing through the doge’s flats (which you will see later), you will reach the staircase leading to the doge’s chapel.

Before entering, stop on the landing of the staircase.

The staircase, which today will appear very humble to you, was once richly decorated. The memory of this splendour can still be seen in Tiziano Vecellio’s fresco depicting St Christopher carrying the baby Jesus on his shoulders.

This is one of Titian’s greatest masterpieces in the palace today, as well as a rare example of a fresco, as in Venice it was preferred to paint on large canvases, due to the humidity conditions that did not allow for the optimal preservation of works created with this painting technique.

The work was executed in 1523 for Doge Andrea Gritti.

Gritti was a much-loved doge and apparently also very good-looking. The doge was not interested in the figure of St Christopher because he was the patron saint of travellers (I remind you that doges were not allowed to travel), but because the saint was also the figure who protected against violent deaths.

Indeed, the doge feared being murdered by one of the husbands of his many mistresses or by other oligarchs in the palace.

However, this ‘amulet’ did not work: the doge died a few months later by suffocating while eating an eel, bisatto, probably poisoned.

Iconographic tradition has the saint depicted while crossing a Palestinian river, but here the scene is set on the Venetian lagoon, on the left we see the Venice skyline, while on the right the Alps are depicted, this is because Titian was a native of Cadore, and he often depicted his beloved mountains in paintings.

The Doge’s Hidden Treasures: guided tour tickets.

Purchase online. Choose the time of your choice. Join the guided tour of the secret terraces and hidden treasures of the Doge’s Palace by skipping the queue at the ticket office.

You can cancel for free up to the day before the tour.

The doge’s private chapel

The doge’s private chapel is located above his flats and next to the senate.

The position of this chapel is somewhat strange, because its apse is located to the west and not to the east, in fact this was not the original position.

The chapel was moved to this side of the palace after the fire of 1573, which developed inside the doge’s flats, in the place where the ‘Hall of Heads’ used to be. The old room was named after Bishop Grimani’s huge collection of Roman busts.

After the fire, the collection was moved, and the chapel was placed.

The renovations were carried out by architect Vincenzo Scamozzi and were paid for by Doge Cicogna (note the stork’s coat of arms inside the chapel).

The chapel was sculpted by Scamozzi, and the statue of the Madonna by Jacopo Sansovino.

Sansovino, however, had passed away in 1570, four years before the fire and 20 years before Scamozzi completed the restoration work, so he did not make the statue for this apse, but it was placed there later.

Apparently the statue was found by his son, Francesco Sansovino, who also worked closely with the palace, as he had been commissioned as historian to study the iconography of the new paintings after the fire.

The rest of the chapel is decorated with a vast fresco, painted later, between 1710 and 1720. In the meantime, it appears that large canvases representing the territories of the Venetian Republic by the painter and cartographer Cristoforo Sorte were housed here.

Initially made for the Senate Hall, the senators, however, tired of having the canvases continually updated, decided to move them here. The maps were later destroyed.

The 18th-century fresco is the work of Jacopo Guarana, an author who is not well known; the truth is that in 1710 the palace did not have enough money to pay Tiepolo, the leading artist at the time.

So Tiepolo proposed sending one of his disciples, Guarina, who worked here with the help of two other assistants, Girolamo and Agostino Menduzzi Colonna, two quadraturist painters-father and son-who made the panels and tromphe d’oeil in which the scene is set.

Guarana blends religious and political themes, the sculptures depicting the symbols of the four evangelists and allegories of good government:

Prudence (the woman with the snake and the mirror), Wisdom (an old woman with books and a hatchet). On the ceiling is depicted Heaven with angels and the lion of St. Mark, the symbol of the triangle of the trinity.

Four women are depicted within the scene:

- The one with the drape holds a scepter formed by two snakes, ending in two wings (this is not the caduceus symbolizing medicine, which at the time was depicted with only one snake, but that of happiness);

- The woman on the left depicted on the parcels is trade;

- The one in the center with the sickle, ear of corn and circle with astrological symbols is agriculture;

- The one with the pink skirt and rudder is navigation.

The very modern message the painter wanted to communicate was to always remind the doge of the importance of the workers, who had built the glory and happiness of Venice.

The Antichiesetta

We continue our guided tour of the Doge’s Hidden Treasures, moving on to the room known as the ‘antichiesetta’.

The ceiling is still by Guarana, while the two gold panels are two works of contemporary art celebrating the years.

The three paintings are the work of Sebastiano Ricci, the last great official painter of the Serenissima, who was commissioned to make the preparatory cartoons for the remaking of the mosaics above the portals of St. Mark’s Basilica.

The large painting is precisely one of the preparatory cartoons.

To restore them, it was decided to replace them with completely new mosaics (unfortunately, the theories of restoration and conservation had not yet developed).

There are nine mosaics on the façade of the basilica, four on the second order and five on the first, corresponding to the five access arches. Of these nine mosaics, only one has been preserved from the Byzantine era, the first on the lower left, above the portal of St Alipius.

Of the five mosaics of the first order, the largest central one depicts the Last Judgement, those on the two smaller sides tell the story of the arrival of St Mark’s body in Venice.

The tale is divided into four scenes:

- in the first the customs officers hold their noses at the arrival of the pork;

- in the second we see the procession of men leading the boat;

- the third scene is the arrival of the body being received by the doge;

- the last scene on the left corresponds to the only original Byzantine mosaic on the façade and depicts the entrance of the body into the church.

The mosaic ”vignettes” should in fact be read from right to left, like Arabic texts.

According to legend, the body was found in Alexandria by two Venetian merchants inside a column. The two merchants smuggled it out of the city’s port to their ship, loaded with goods.

To circumvent customs controls, they decided to hide the body inside a cargo of pork (this animal is in fact considered impure by Muslims), and in this way customs controllers would certainly not inspect it.

So, they returned to Venice, where St Mark’s body was received by Doge Agnello Partecipazio, who chose the area of St Mark’s basin to erect the Basilica that would house the Saint. Partecipazio’s son and future doge, Justinian, would eventually move the Government Palace next to the Basilica, the first nucleus of the Doge’s Palace.

Meanwhile, the seat of government was housed at Rialto, in one of the nobles’ private residences.

The preparatory cartoon depicts precisely the scene of the arrival of St Mark’s body.

The guided tour of the Doge’s Palace Hidden Treasures ends here.

Doge’s Hidden Treasures: things to know before visiting

Before starting the tour of the Doge’s Hidden Treasures, a brief introduction to the governmental structure of the Republic of Venice and the figure of the doge will certainly be useful.

As you will know, the palace was the main seat of the Venetian government, the latter being divided into several councils.

The main council was the Great Council, which brought together all Venetian citizens with the right to vote, and thus also the right to be elected to government positions. These people could only be men who had reached the age of twenty-five, and especially nobles, born into one of the traditional Venetian patrician families.

For Venice, despite declaring itself a republic was to all intents and purposes an oligarchic regime, and the governmental structure, especially from 1002 – 1003, consisted of a regime governed by a circle of nobles, always the same.

The Great Council gathered in its assembly many people, between 1200 and 2000, all together at the same time. The Great Council held legislative power and elected all government offices and the doge.

The doge was primarily the head of the Venetian army, the name ‘doge’ in fact derived from the Latin word dux, meaning leader. In the early days of the city, still under the Byzantine Empire, the doge was just that, later becoming the representative of the government, as a prime minister is today. His vote counted no more than that of the other members of the assembly, the only difference between the doge and the other senators was that he was elected for life.

In Venice, there were only three offices for life:

- that of the doge;

- that of the nine procurators of St Mark’s;

- that of the Grand Chancellor, the latter being the only representative of the Venetian bourgeoisie (and as a bourgeois he had no right to vote).

To prevent doges from remaining in office for too long, they were usually elected at a very advanced age, the large number of doges that followed one another in the history of Venice (120 in total) is precisely due to their seniority, there were doges that lasted a few years or even a few months.

The doge was not a king and did not wear a crown, but rather a ducal horn (a headdress with a shape reminiscent of a Byzantine helmet), and this was because, as mentioned earlier, this office was initially intended only for the command of the army.

The doge together with his six privy councilors formed the Minor Council. The Minor Council, together with the senators (a body consisting of forty to sixty people depending on the century) formed the executive of the Venetian government, which met in the hall of the Maggior Consiglio, on the fourth floor of the palace, above the doge’s flats. The judiciary, on the other hand, was divided into several magistratie, called quarantie. From 1310 all the quaranties were controlled by another very powerful council, the Council of X, so called because it consisted of ten members, who held office for one year and were not eligible for re-election for a subsequent term. This council was formed to ensure the survival of the regime, officially established in 1297, with a historical event called the Serrata del Maggior Consiglio. Until this date in Venice those who became particularly famous or rich could acquire noble titles and the right to be part of the government. The term ‘serrata’, which means ‘closure’, alludes to the preclusion of government offices to those who were not members of the traditional patrician families.

Thirteen years after this event, a nobleman who could attend government meetings, Baiamonte Tiepolo, organised a conspiracy to make the council vote in favour of reopening the Venetian government.

The conspiracy, together with an attempt to assassinate the incumbent doge, failed, and the regime, in order to prevent further coups, established the Council of Ten. The Ten also formed the secret service and had a large number of emissaries abroad and secret codes to transmit information.

The doge’s flats occupied a very small space compared to the palace, whose main function was as the seat of government. However, it was not only this, it also housed the courts, all the magistracies, the great chancellery (the apparatus of the central bureaucracy of Venice and its territories), the archives and the prisons, the latter would be moved only at the end of the 1500s to the new prisons, connected by the Bridge of Sighs.

Doge’s Hidden Treasures Tour: tickets and reservations

If you are interested in participating in the Doge’s Hidden Treasures tour, online booking is recommended. By purchasing tickets in advance, you have the opportunity to enter the Doge’s Palace skipping the queue at the ticket office and easily take part in the guided tour.

Ticket reservation prices are as follows:

- Full price ticket: 38€ (the ticket includes access to the Doge’s Palace in addition to the guided tour).

- Reduced ticket price*: 26€ (the ticket includes, in addition to the guided tour, also access to the Doge’s Palace).

*Residents and those born in the Municipality of Venice; children from 6 to 14 years old; students from 15 to 25 years old with student card; citizens over 65 years old; RollingVenice Card holders; VeneziaUnica Pack holders; MuveFriend Card holders, purchasers of tickets for St Mark’s Square Museums, Museum Pass; Clock Tower ticket holders; I.C.O.M. members, staff of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities, ISIC – International Student Identity Card holders.

Visiting the Hidden Treasures of the Doge’s Palace: frequently asked questions

No, access to the Doge’s Hidden Treasures is only permitted in the presence of a qualified guide. It is not possible to access them independently.

The interior structures may have restricted spaces and some passages may be on several levels, often connected by narrow, steep stairs. These environments may not be suitable for people with disabilities, movement problems, claustrophobia, vertigo or cardio-respiratory conditions. They are also not recommended for pregnant women.

Only children over the age of 6 are allowed to enter.

Yes, the ticket also includes admission to the ordinary visit of the Doge’s Palace in Venice.

Yes, you can visit the Doge’s Palace independently before the start of the “Doge’s Hidden Treasures” tour by going to the meeting point at the pre-arranged time for the guided tour.

Doge’s Hidden Treasures Tour: conclusions

Well, we have come to the end of the Doge’s Palace Hidden Treasures tour of Venice.

You can now continue your visit in the rest of the museum. I advise you to go back and go to the entrance of the tour, in the square atrium, to make sure you don’t miss a single room.

If you need more information, read more about the Doge’s Palace Secret Itineraries Tour.